“You think you can fuckin’ steal from me, donkey dick?!” Then that unmistakable sound of a hard fist raining down a bone-crunching blow to the face. “I’ll kill you and your whole fuckin’ family!”

The “donkey dick” having the shit kicked out of him was none other than John Holmes, the Elvis Presley of pornography. The guy screaming “fuck” every other word was Eddie Nash, the drug lord, in whose San Fernando Valley pad the scene was taking place. The fists that were making raspberry jam out of Holmes’s face belonged to Greg Diles, Nash’s 400-pound security guard.

“I trusted you! We were brothers! You fucking stab me in the back like this?! Tell me or I’ll cut that fucking freak-show dick of yours off right now!”

It was after midnight on July 1, 1981, and even though Scott Thorson had been excused to the living room, every single sound coming from the neighboring bedroom was viscerally audible. Scott was high as hell on crack and more terrified than he’d ever been in his entire life.

A Life in Glitter

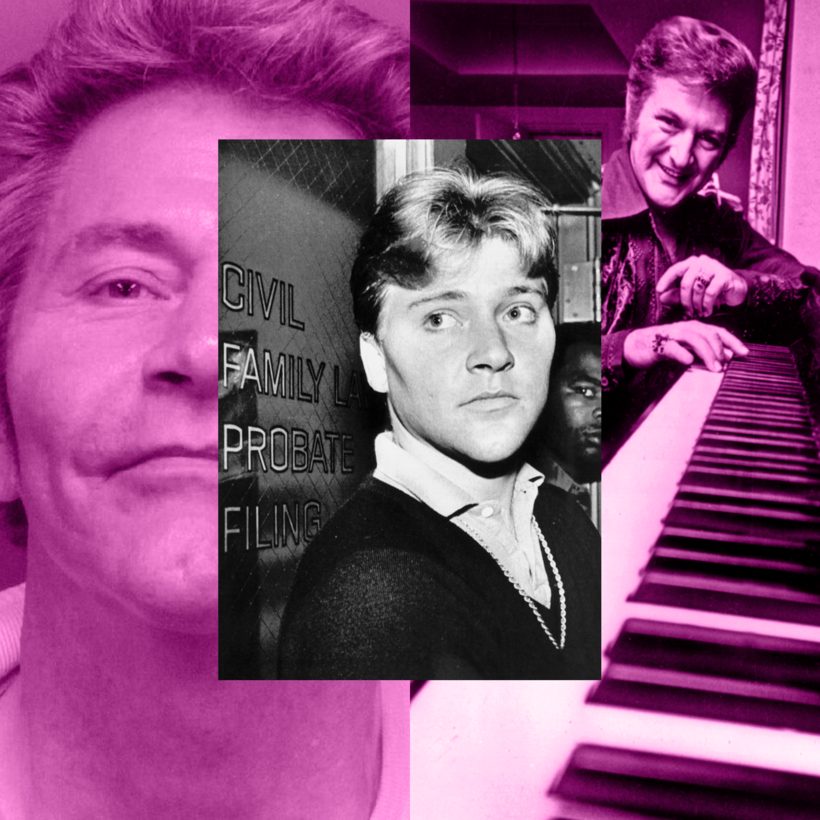

Scott Thorson is now 65. In late 2020, he was granted an early release after serving nearly seven years in a Nevada state prison for credit-card fraud. Last year I began interviewing him for a book project and quickly understood why he’s been referred to as the “Zelig of Awful.” “I mean, how can one kid from Wisconsin find himself in as many outrageously fucked-up situations as I have?” says Scott.

Thorson was a teenage runaway bouncing around West Hollywood’s “Boystown” in 1977 when he met Liberace—the profoundly flamboyant, deeply closeted piano prodigy who at the time was the highest-paid entertainer in the world. Liberace was 57, while Scott had just turned 18 and was reeking of parental neglect after a childhood spent in and out of foster homes and orphanages. Scott was in search of a father, and Liberace wanted a son. A son with benefits.

(Scott chronicled their stranger-than-fiction relationship in his 1988 memoir, Behind the Candelabra: My Life with Liberace, which was made into a 2013 HBO film directed by Steven Soderbergh and starring Matt Damon and Michael Douglas.)

Ostensibly, Liberace—or “Lee,” as Scott called him—hired the cute, impressionable young twink as an employee. As part of the show, Scott was the servile chauffeur, driving a bejeweled Rolls-Royce 20 feet from the stage, whereupon he’d exit the car—dressed like a member of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as imagined by Tom of Finland—to humbly open the passenger door for Liberace.

The main attraction would then emerge, wearing the most ostentatious furs and jewelry imaginable, ready to take his seat at a custom-made, crystal-laden piano with the trademark candelabra atop.

Life with Liberace didn’t have a happy ending. Liberace sought to legally adopt Scott and successfully pressured him into getting plastic surgery so that Scott would resemble his patron more closely. In order to help Scott lose weight, a cosmetic surgeon prescribed the “Hollywood diet”—pharmaceutical cocaine, amphetamines, and quaaludes—before Liberace unceremoniously dumped him, in 1982. Scott sued Liberace in America’s first same-sex palimony suit. He received a paltry settlement and an expensive drug habit.

Beyond the Candelabra

But back in 1980, the doomed pair were still together. Scott was hopelessly bored with domestic life, so Liberace suggested that he go into business with Eddie Nash—a Palestinian immigrant who was arguably the No. 1 club owner in Los Angeles at the time. Nash’s joints included the Starwood, Soul’d Out, Paradise Ballroom, Seven Seas, Ali Baba’s, and the Kit Kat, to name just a few. Black club, gay club, rock club, strip club, tiki club—whatever. What Liberace didn’t know was that Nash also happened to be the biggest drug lord in all of Los Angeles.

While Nash already had a few celebrity clients, the addition of Scott’s high-profile contacts via his life with Liberace meant the pair quickly became the go-to drug suppliers for Hollywood and the music industry. They dealt copious amounts of pure Colombian to everyone from John Belushi to Richard Pryor, from the members of Fleetwood Mac to Rod Stewart.

“Back then, if you heard sniffing outside the bathrooms at the Chateau Marmont, I guarantee it was our product being snorted,” says Scott. “Drugs just weren’t taboo. If a star performer requested coke on their rider, trust me—no crew would think to stock their dressing room with Coca-Cola.... Everyone was snorting, shooting, fucking, and sucking like there was no tomorrow.” Scott says Nash was the first dealer to offer freebase cocaine, which gave way to crack. Scott and Nash weren’t just selling this novelty, though. “We were smoking the shit outta it!” says Scott.

A cosmetic surgeon prescribed the “Hollywood diet”—pharmaceutical cocaine, amphetamines, and quaaludes.

In their celebrity-clientele roster, there was one customer who was easily the most crack-obsessed—John Holmes. Video hadn’t yet killed the porno star, and, in Los Angeles, smut remained lucrative and ubiquitous. Certain porn stars’ names on a Pussycat Theater marquee could still draw a ticket-buying crowd, eager to consume hard-core films in public. Of all the names, Holmes was by far the biggest on the blue screen. How big? “Bigger than a pay phone, smaller than a Cadillac,” according to Holmes. By the summer of 1981 he had a big, $1,500-a-day crack dependency too.

Even within his own seedy industry, Holmes was considered an untrustworthy weasel. “But he had a certain slippery charm, and Nash liked having him around for the pussy he’d attract,” says Scott. “As the gay business partner, that wasn’t exactly my department.” Holmes claimed to have slept with 14,000 women, and Nash thought it was pretty neat having the Porn King around as a regular fixture. He’d always address Holmes as “my brother.”

However, Holmes was broke and had burned bridges left and right. Even his bread and butter became impaired as word got out that he was going limp on sets as a result of the drugs. The Porn King had been reduced to a Porn Jester. With few places to go, Holmes started spending more time at a house on Wonderland Avenue in Laurel Canyon. It was rented by a scuzzy group of room-temperature-I.Q. criminals and fellow addicts known as the Wonderland Gang, whom Holmes would finagle drugs from when his credit line with Nash was over-extended.

On Sunday evening, June 28, 1981, the Wonderland Gang was particularly desperate and dope sick. After selling a pound of baking soda as cocaine for $250,000, bounties had been placed on their lives, and with no drugs or money left, a score was seriously needed. Holmes had convinced them he had the perfect piece-of-cake heist: ripping off Eddie Nash. “The Wonderland Gang was stupid enough to listen to him,” says Scott.

Holmes provided them with a floor plan of Nash’s three-bedroom tract house in the San Fernando Valley, as well as a promise to leave the sliding door unlocked on his visit prior to the planned robbery. In exchange, Holmes would be able to hang back at Wonderland and get a finder’s fee cut of the loot. He showed them where Nash’s valuables were located—a Rembrandt painting, a jade-and-ivory collection, sterling silver and jewelry. Not to mention lots of cash and drugs.

The Wonderland Gang managed to collect $400 between them for Holmes to take to Nash’s under the guise of a drug purchase. He left Wonderland at midnight but didn’t return to give them the go-ahead until just after dawn. He’d spent six hours hanging with Nash, smoking the rock he’d just bought with their dough.

With the green light, four of the Wonderland Gang—Ron Launius, Billy Deverell, David Lind, and Tracy McCourt—drove a stolen Ford Granada, with barely enough gas in the tank, 1.6 miles from their Laurel Canyon HQ to Nash’s house on Dona Lola Place. It was around 8:30 a.m., Monday morning. While normal people were heading to work, these gun-wielding bozos opened the unlocked sliding door and walked right into the home of Los Angeles’s most powerful drug dealer.

The armed invasion was a brutal one, during the course of which Nash’s security guard, Greg Diles, was shot and injured. The gang made off with almost $1 million in cash and other valuables, as well as a mountain of drugs. When they returned to Wonderland Avenue they actually thought they were out of the woods.

The Porn King had been reduced to a Porn Jester.

Two days later, Scott was getting ready to travel to Lake Tahoe to perform his usual onstage chauffeur shtick with Liberace when he realized his personal drug stash was depleted. He chartered a last-minute Learjet from Las Vegas to L.A. so that he could pick up a pound of cocaine from Nash for the trip. “Hey, you never wanna run out of the essentials when traveling!” says Scott. “Lee was making $23 million annually for 18 weeks of work in Vegas, so me hopping onto a private plane for an errand was the equivalent of Joe Schmo getting into his sedan.” When he got to Dona Lola Place, Scott immediately knew he’d stepped into the middle of something horrific and life-changing.

“Those motherfuckers! Those motherfuckers fucking robbed me, Thorson!” screamed Nash, in his trademark attire—an open maroon silk robe and a pair of Speedos. (If all of this is starting to sound familiar, that’s because Alfred Molina portrayed a Nash-like drug dealer in Paul Thomas Anderson’s 1997 film, Boogie Nights. Mark Wahlberg’s Dirk Diggler was based on Holmes.)

Nash was ranting and raving and waving a gun around, saying how he was going to murder the thieves. “The only times I’d seen him with a firearm before was for attention, when, high, he’d shock guests by playing Russian roulette with himself,” says Scott. “This was different.” Even though he’d been his business partner for some time and they’d partied together plenty, somehow Scott had managed to avoid the violent side of criminality until that day.

Against any better judgment, Scott hung around with Nash to get high. After a while, Diles barged in with a rattled-looking Holmes, who he’d seen wearing one of Nash’s stolen rings. “Big dick, small brain!” says Scott. Diles beat Holmes in the bedroom while Nash interrogated him. It took almost no time at all for a full confession. Once names were named, Nash ordered Diles and some of his other thugs to take Holmes to the Wonderland Avenue house and kill everyone inside. “They even borrowed my Bill Blass Lincoln parked outside for the drive,” says Scott. “In that moment it hit me—I was officially a witness.”

Scott stayed put, acting as obsequiously toward Nash as possible so as to not raise suspicion and make the madman think of getting rid of a loose end. On the plus side, staying with Nash meant being able to do more drugs. “Hey—if I was gonna fear for my life, I sure as shit didn’t wanna do it sober!” says Scott.

Before he knew it, Diles, Holmes, and the rest of the wild bunch returned covered in a Peckinpah-esque amount of blood. They recounted the violent revenge in nauseating detail, according to Scott, with Diles even boasting that the threads from the metal pipes they used to beat the Wonderland Gang to death left visible indentations in their pulverized skulls. “I was told to keep my fucking mouth shut—which I did dutifully for six years,” says Scott.

He did, however, immediately confide in Liberace about what went down. “It understandably made him practically shit his pants,” says Scott. The anxiety only got worse once the media circus surrounding what was dubbed the “Four on the Floor Murders” was set in motion. It wasn’t long before Liberace dumped, fired, and evicted Scott, leaving him nowhere to go except Nash’s suspiciously open arms.

“If I was gonna fear for my life, I sure as shit didn’t wanna do it sober.”

While Scott initiated his palimony suit against Liberace, his role in Nash’s drug operation grew. Nash was obviously an immediate suspect after the murders, and following raids on his house and nightclubs he was apprehended, leaving Scott in charge of running the day-to-day operations. “Imagine that—I was the most trustworthy person in his orbit!” says Scott. Nash had plenty of powerful friends, both in law enforcement and local politics, and there wasn’t enough juice for a prosecution. So he was released on parole, more paranoid than ever.

Being his right-hand man became an exponentially more frightening position for Scott, particularly as their activities expanded to partnerships with street gangs such as the Black Guerrilla Family and the Bloods. “Now we weren’t just dealing to the town’s showbiz elite,” says Scott. “We were laying ground zero for L.A.’s crack epidemic.”

Scott remained Nash’s loyal foot soldier for more than half a decade. “That all came crashing down when one transaction went sideways, and some women in one of the crack houses we were supplying to were beaten, raped, and robbed,” says Scott. “Yet again, I’m just in the wrong place at the wrong time!” Nash initially posted bail for him, but then revoked it—throwing Scott under the bus for the crimes he says he didn’t commit.

While he was awaiting trial, the unsolved Laurel Canyon murders were still making headlines, with Nash as a major suspect. In search of a deal, Scott broke his silence, becoming a star witness in exchange for all charges against him being dropped.

Nash was charged with planning the murders, and Diles was named as a participant. Scott’s detailed testimony was persuasive, though the trial ended in an 11–1 hung jury. “I suspected that Nash paid off that lone dissenting juror,” says Scott. Nash was acquitted. And Scott was forced into the federal witness-protection program.

A New Kind of Drug

Scott’s life story from this point on produces a dizzying one-man Rashomon effect. The sheer breadth and absurdity of Thorson’s adventures while under federal protection and afterward stretch credulity. But while details don’t always remain consistent, the main vectors check out. Suffice it to say that everything should be taken, and probably was taken, with a grain of white powder.

Scott was sent to rural Florida under an assumed name and became an employee of a rescue mission associated with an evangelical church where the down-on-their-luck came to be “saved.” “The head pastor saw dollar signs in his eyes when he heard my story,” says Scott. It was the perfect tale to raise the congregation’s profile: Evil Hollywood turns innocent young boy into a homosexual drug addict, but he escapes that sin and soul corruption thanks to Jesus and is now a straight-as-an-arrow born-again Christian. Scott became the church’s poster child.

Amazingly, Scott started making a name for himself on the preaching circuit and developed a huge following, raising hundreds of thousands for the church while traveling around the country on private jets to sermonize onstage at all the biggest God-fearing events. When the feds eventually saw his mug on TV, televangelizing with Billy Graham and Pat Robertson, they were livid. Scott was keeping the opposite of a low profile and making it literally impossible for them to protect him from Nash and his cronies.

“The phoniness was getting to me, though,” says Scott. “At least selling drugs to addicts was a more honest racket than hawking Jesus to yokels with these grifters.” Scott was still in witness protection, so he says he began clandestinely running drugs with the cartels—connections made while working with Nash—under the feds’ noses. “What easier way to transport narcotics than while traveling with federal agents?!” says Scott. “You can get through an airport lickety-split.”

According to Scott, Nash quickly caught wind of his former partner’s return to the criminal underworld and tracked him down. One night, in 1991, at a Howard Johnson’s in Jacksonville, Scott heard a knock at the door. When he opened it, a crack dealer—who Scott insists was a hired hitman of Nash’s—shot him several times. By the time the ambulance arrived, he says he had been dead for six minutes. He was revived but lay in a coma for six months.

“Selling drugs to addicts was a more honest racket than hawking Jesus to yokels.”

An evangelical Christian named Georgianna, from Maine, who Scott says had seen him appear on the Billy Graham crusades and The 700 Club with Pat Robertson, talked her way into his hospital room during his recuperation by claiming she was a pastor who’d come to pray for him. When he was finally discharged, she encouraged him to come and live with her.

Scott was temporarily paralyzed from the waist down with significant cognitive damage, so the road to recovery was long and hard, requiring many surgeries and much therapy. Disabled and depressed, he convalesced at her home for nearly 12 years. “It was the most fucking boring time of my life!” says Scott. “I had to pretend to be straight for her sake, and she was constantly trying to pressure me for marriage.” Prescription painkillers became his only escape.

Scott says that one day in 2003 the phone rang at Georgianna’s in Portland, Maine. “It was Nash’s attorneys—the son of a bitch had tracked me down!” Fearing for his life, Scott called the feds and said he wanted out of Maine and to return to California with their guaranteed security. According to Scott, the marshals had had it with him and declined. “So,” he says, “I enlisted the Mafia for protection.”

Scott requested a sit-down with an Italian crime family he knew from his days with Liberace, as they owned many of the theaters they had played at. Scott claims they agreed to adopt him as an associate—he would run drugs for them—and in no time at all he was in Palm Springs, buying from the cartels and selling for the Mob.

Freed from a captive heterosexual life, he started off carefully enough but eventually got sloppy and, during a night of hard partying, got pinched with 10 grams of meth on him. The authorities tried to throw him away for life, citing the RICO Act (a racketeering charge used to nab mobsters), but Scott’s Mafia family paid for his legal defense, and since the prosecutors didn’t have sufficient proof of racketeering, Scott’s sentence was reduced to four years in prison. Charles Manson, the perpetrator of another infamous Los Angeles mass murder, was in the cellblock opposite, according to Scott.

Epilogue

Nash had also been arrested on RICO charges, in 2000. A year later he entered a plea bargain, admitting to bribing that lone holdout juror in the Wonderland-murders trial, and pleaded guilty to money laundering and wire fraud. Additionally, he admitted that he’d dispatched his associates to Wonderland that night to take back his stolen property, but he denied ordering any murders. He was sentenced to 37 months and paid a $250,000 fine. “Boy, oh boy, does it help to have friends in high-up places,” says Scott. Nash died in 2014 at the age of 85.

When Scott was finally released from prison in 2012, his brief experience on the outside was a mixed bag. His memoir was made into an award-winning movie, but he was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer and began snorting meth again. Then he got caught using a stolen credit card and was charged with 27 counts of fraud. He spent another eight years in prison but did, finally, get clean.

“I’ll tell ya, it’s a fucking strange thing being the only survivor of all this.... bullets, cancer, crack, prison—you name it. My whole life I’ve been just a coin toss away from death. Yet I’m somehow still here,” says Scott. “Why? Hell if I know!”

Spike Carter is a writer and filmmaker. He is currently working on a book with Scott Thorson about his role as a witness to the Wonderland murders